http://mourninggoats.blogspot.com/2010/ ... rella.html

[ view entry ] ( 3633 views ) | permalink |

( 3 / 6024 )

( 3 / 6024 )In every walk with nature one receives far more than he seeks.

John Muir

We must not sit still. We must take journeys and we must take risks. Our souls require starry nights beneath breathless trees and wild places. We must go to the woods when we can, and drink from the rivers. Now, more than ever before, we must return to silence, and be truly alone with ourselves.

I want to tell you a story. Because no story is true until it is told, and this is my story; I am its hero and its villain. Every once in awhile something happens to me that causes me to stop and wonder. Who am I? That is the only question for us. And there is no one who can answer but ourselves. Where is that answer? Can it even be answered? Can it even be asked?

I went to Yosemite National Park. Three weeks ago now. I went with three of my oldest friends and one new one. Yosemite is a beautiful place filled with trees and grasses and great mountains of exposed granite. I love it there. I love being outside at night under a sky so filled with stars that beneath them, I feel God. I like the feeling of fragility and smallness I get when I am out in the woods. Being in nature makes me feel a profound sense of connectedness and spirituality. But also it makes me feel a little scared. There is something terrifying about being in the wild. The earth is a very old place. You realize that things like rivers and rocks and trees have been here doing what they do for millions of years before we ever came along and they will be here millions of years later, long after we have disappeared. Man is very small. We think we have conquered nature but that is a foolish idea. Man is arrogant and selfish. And I among them.

My friends and I went back into the woods. We picked up the John Muir Trail at Tuolumne Meadows and hiked six miles along the Lyell Fork of the Tuolumne River through a U-shaped canyon cut by a glacier 10,000 years before Jesus. We carried everything we needed to survive on our backs. My pack weighed 40 pounds. I wore a straw hat. The sun was hot and I carried the groupís only water filter Ė a necessity at that elevation for the water in the streams and creeks was not safe to drink with all the pack animals that used this trail. I also carried two other things; which seemed at the time foolish indulgences. I brought by digital SLR and borrowed a set of hiking pole from one of the other men.

We hiked for three hours and pitched our tents next to the river. At this time of the year it was more of a stream. We cooked our food over an open fire and slept in the cold. Over night it was 24 degrees and when we woke the following morning the water in our pots had frozen over. Our tents were covered in frost.

The Yosemite back-country is very wild and very quiet. We barely heard a sound for four days. There were some birds, but not many. On the first night we heard coyotes. The sound of a coyote is one of the loneliest sounds in the world. Itís not so much the howls that get into me as it the throaty yips and howls, coming down from the hills that surrounded us. It felt like we were being watched, and judged. Mostly we heard the sound of the river. That is a wonderful sound to fall asleep to Ė a river. If you could hear the sound of a slow river running through boulders and pebbles every night youíd never have a problem falling asleep.

On our first full day in the back-country we took a long hike into the surrounding mountains in order to acclimate to the altitude. We were up around 9,000 feet and hoped to scale Mt Lyell on Saturday. At 13,114í, it is the highest peak in the park. I had climbed once before when I was 24 and my memory of that grueling hike was still fresh enough to fill me with a sort of dread. It was a tough hike then and I doubted whether I could make it now. I stopped drinking and smoking more than two years ago so one could argue I was in better shape, but other than walking I donít get much exercise. Robert, our group leader, is a marathoner and he was absolutely Hell-bent on making the ascent. I decided I would take it one day at a time.

We hiked over eight miles that second day and had our lunch next to a small lake so blue youíd swear it was a dream. We were preparing ourselves to climb the peak. When you find yourself at high altitude Ė over 10,000 feet above sea level - it is difficult to breathe and your heart rate quickens. You get headaches and sometime itís hard to see. You can see spots before your eyes and your ears ring incessantly. We wanted to spend a day in the high country to get used to this altitude. I was with four other guys, three of which I have known since I was 15 years old. We crossed the country together in our early 20ís and made a home in California. We have stuck together through some very tough times and managed to remain close despite many changes to our lives and circumstances. Yosemite seems to have become our rite of affirmation and renewal. We go there together when we can. I think we tell ourselves itís to get away for a while and commune with nature but what I really think its about is a reaffirmation of our bonds as friends, as brothers really, because thatís what we are.

On Saturday morning, September 11th, we rose at 6:30am and left our base camp for Mt Lyell. It was about 30 degrees when we set out. We could see our breath and there was a beautiful layer of crystalline frost covering the meadows. It was very quiet. We hiked for an hour in the silence and then shed some of our clothes. We stripped down to shorts and tee-shirts. I was wearing a straw cowboy hat and I had my bulky camera slung from my neck. I also had the hiking poles. These are like the poles you see people use for skiing. They help you to keep your balance on narrow, rocky trails. It was the first time I had ever used such poles. They were on loan to me from the fifth member of our party, Doug O., a college buddy of my old friend Robert. These poles, and his generosity, would wind up saving my life.

We began to climb at about 8:30am. I felt good enough to try, and knew I could always stop and turn back if I felt dizzy or weak. It was a very long climb up out of the meadow, over switchbacks that went on for miles. Despite the cold we were sweating. At several points we stopped and measured our pulse rates. Mine was consistently above 150. But I was moving slow and lagged behind most of the time. Of the five of us I was the least prepared and the least fit. Rob and Mike run marathons. Phil works out routinely at a gym. Doug is an avid surfer. It was disheartening at times for me to be so far behind. But I enjoyed the quiet and the solitude at the back of the line.

The sky was perfectly clear and blue. that morning We stopped to dip our heads into an icy cold creek fed by the runoff of melting snow. Then we continued our climb. We climbed and we climbed. The terrain was very rocky and uneven. The trail was also dusty and Iíd often gargle with water to wash the grit off my teeth. It was hot in the sun and cool in the filtered light of the pine forests just below the tree line. We hiked through wooded meadows and quiet pine forests. After a couple hours we stopped because some of the guys had blisters. They had to take off their shoes and apply mole-skins, which are these sticky bandages that help cushion a blister. We were well over 10,000 feet high now and I felt very good. I was surprised at how good I felt. We were sitting in a place called Horseshoe Canyon, the very spot we had set up our base camp 20 years before. You can see the Lyell Glacier from this spot and the peak of Mt Lyell itself rising above it. Thatís where we were headed. I had been in doubt about my ability to summit this morning. But now I was sure Iíd make it. I felt clear-headed and strong.

Then we began to climb again. We climbed for another two hours. During that time it had become increasingly difficult to walk. It was steeper, rockier. We left the worn trail where it turned toward Donohue Pass and moved out onto an unmarked granite plateau where the terrain was a mixture of loose rock and dense, short-cropped grasses. We scaled our first big obstacle field here. Imagine a hill a hundred feet high composed entirely of boulders. The footing is tricky and youíre often hopping from stone to stone where a poorly timed leap would mean instant shattered ankle. At the top of this boulder pile we encountered our first snow.

It is exhilarating to hike over snow in shorts and a tee shirt. But the glare can be blinding. By now we were so exhausted that speaking aloud was difficult. Communication was accomplished with nods and grunts. One of our party, Mike, had been setting a blistering pace and was ahead by several hundred yards. I could see his white shirt moving slowly upward, just this spec of white rising methodically up and up. Then he stopped and waited.

We rested and had our lunch about 1500 feet below the summit. We ate nuts, salami, tuna and cheese. We drank a lot of water. We had to pump it from a small seepage created by melting snow and ice. I had the only pump. To drink unfiltered water would risk infection with a microbe called Giardia Ė which I have gotten once before. It is a terrible illness that lasts two weeks and in that time you canít eat anything but soup and you double over in gut pain and you just want to die. We filled our water bottles here for the last time before the ascent. The air is so thin and we were sweating so much that we had to be constantly drinking to avoid dehydration. We sat on a large boulder and drank and ate in silence. Breathing was difficult. We stared up at the summit. We didnít even discuss what we were about to do.

Only later would I realize that this was the moment where everything fell apart. We had no plan for how to make the ascent. We had no communication or buddy protocol. We had no time schedule or turn back deadline. We foolishly left the two-way radios in the car, thinking weíd not need them. We simply saw this mountain and assumed we could waltz right up to the top. And as we sat there silently eating our lunch, there was no discussion as to what weíd do next. Looking back on it, it was a strange moment. We did not come together as a team, instead, we seemed to individualize, to fracture. Not due to any rift or disagreement, not due to anything discernible at all. And at that point I felt alone. Maybe I felt that way the whole time, like I was not quite part of the others. Since I stopped drinking this feeling has become more prevalent in me. The whole world seems to revolve around the consumption of mind-altering substances and pastimes, and when you stop, when you remove the veil and simply exist naked before each moment in time, you begin to see how most people exist in a dreamlike state of denial. I often feel like the protagonist in a zombie movie, or Invasion of the Body Snatchers. All around me are these beings whoíve been infected, and I struggle to blend in, to not draw attention to myself. I am not saying that these men, my friends, are zombies, and I do not classify them among the walking dead who go about their lives in pursuit of attention and affirmation. I love my friends. But I felt separate from them, and it was a self-imposed separation. I am no longer the boy I once was.

It would be wrong to call what I did next a decision. Because I didnít think. I had no conscious thought. I just got up, packed my things and started climbing. I left my friends. I told myself I was going to get a head start on the others because was worried about being left behind. But the bottom line was, I went rogue. I started up the mountain alone, thinking that my friends would surely catch up and pass me before I even reached the glacier (below Mt Lyell is a glacier ľ mile square that you must cross or climb in order to reach the summit on the rocks above it). But I was wrong. I would not see any but one of them again for seven hours.

I walked across a talus field Ė a vast expanse of boulders and broken rock Ė each one as big as a Volkswagen bug. If I took one wrong step my leg would wedge into a hole between sharp rocks and Iíd likely break it. But the hiking poles were helping me to keep my balance. I was moving well. I am good on rocks and had established a smooth rhythm. I was really moving well and relishing the solitude. I felt so good, hopping from stone to stone. My body felt alive and healthy. I was running on all cylinders and I had a second wind. It seemed I would not only make it to the top, but I might even be the first to get there. After about thirty minutes of very fast hiking I found an abandoned backpack hidden in the rocks. I thought that maybe someone had come up early, before us, and was already making their approach to the summit of Lyell. This made me feel a bit disappointed because I didnít want to share the summit with anyone else. I didnít want to see another human being, and here was this backpack, evidence that other people were here before me. But then I became afraid. I thought what if this hiker was dead? What if I found his body wedged in the rocks? That feeling persisted and I began to feel the gravity of what I was doing. But I kept going.

I continued to climb over these sharp rocks and I could not see my friends. They must have taken a different route up, I thought. I was sure they must have already passed me and were perhaps already on the glacier. This spurred me to move even faster. I climbed up over the boulders with an even greater urgency and finally cleared them, arriving at a huge open field covered by deep snow.

I had to cross the snow in order to access the glacier, and it was hard to do. The snow had melted and frozen so many times over that it was really more like ice. It was brittle and prone to cave in under my weight. I carefully walked across it, for maybe 100 or 200 yards and then I found tracks. I could tell they were fresh because the snow was still wet and glistening where the foot had broken through. The person who left them had been wearing crampons - spiked bottomed attachments that clip onto the sole of your shoes that are designed for walking over ice and hard packed snow. I was buoyed by this discovery. I knew that I was on the right path. I looked back over my shoulder and still could not see my friends. Where the heck were they? They must have taken another path. I realized that I was first to the glacier and that if I kept going like this I would be the first to the top. My ego was taking over. My ego was affecting my decisions. I was taking risks on the glacier, moving too quickly, jumping, plodding upward without thinking.

The Lyell glacier is not flat but pitched at about 30 degrees and because of the action of the wind and the melting and re-freezing of the snow, its entire surface was covered in sharp spikes of ice - a scalloped pattern of razor sharp ridges that were about 1 to 2 feet deep and about the size of an oval bathroom rug in diameter. There were thousands and thousands of these ice scallops across the glacier and each was filled with slushy, frozen water. The shallow ones are called snow cups and the deep ones with the sharp peaks (we were later told) are called nieves penitentes Ė an Argentinean term that refers to the pointed hats of the nazarenos Ė a religious order called the penitentes (as it turns out the nieves penitentes are found only in the dry Andes).

The sun was high now and the ice was melting fast. I could hear the water running beneath the glacier in paces and I had to be careful where I stepped. A false step here could mean a soaked foot, or worse, a slip that would send me tumbling end over end down the glacier, bumping over the sharp, glass-like edges of the penitentes. I used my ski poles to test each step and I placed my feet down strategically. I made slow but steady progress up the glacier, working my way diagonally across it. I was heading for a saddle of rock and snow at the far right of the mountain where I had made this ascent 20 years before. It took me about a half hour to get across and when I was more than halfway up I finally saw the others. My friends had just approached the glacier. I could see them as tiny specs below me. I was ahead of them. Way ahead. And I knew then Iíd beat them to the top if I just kept moving. Again, ego. Pride. Arrogance.

When I got across the glacier and reached the saddle between Mt. Lyell and Mt. McClure, I discovered I was very tired. My breathing was strained and rapid. I was hopeful of finding a clear path up the mountain from this side, but what I saw there literally took my breath away. Over the edge of the rock saddle was a sheer drop-off of at least 1000 feet straight down to oblivion. You cannot understand that paralyzing feeling of vertigo until you are in a situation like this. Your body reacts unconsciously to a sudden great height by revolting and refusing to obey. Your head instantly swims and your belly flops over and your center of gravity begins to warp and blur. This was the first moment in which I was truly afraid. I could not take another step in that direction. I could not approach the mountain from that side Ė and that was the recommended way up. I was terrified and felt the first pangs of panic break loose from my gut. That is something you cannot let take hold. Panic will cripple you as sure as a blow to the knees. I backed away from the edge, suddenly aware that my full weight rested on the tips of my toes, dug in as they were into slush. If I slipped here I was dead, and that was a fact.

I had a choice to make. I could attempt to go back down across the glacier from the direction in which I came or I could try to find another route up to the peak. I looked to my left and saw a patch of snow that did not appear to be completely iced over. I thought that if I could make it to that patch of snow I could climb to the base of the rocks. Conditions were changing rapidly and I knew I had to act. The smart thing to do here would have been to go back down, but I could see my friends now, making their way up the glacier and I did not want to retreat. Ego. I had to make it to the patch of snow to my left. I donít know why I thought this. It was a foolish move, because once across that span of snow I could not turn back again.

I used my ski pole to chop away footholds in the ice and I crossed the snow gingerly. I found myself at the base of the rocks but there was something there I did not expect. The snow all along the rim of the rock was clear, solid ice. It was too slippery to walk on in regular hiking shoes. If I had the crampons Iíd have had a tough time crossing it. Without them it was impossible. I was then faced with another choice that led me to a second foolish decision. I could try go back the way I came or I could climb up the rock face in front of me. It was a sheer granite wall. I chose to climb.

I found a crevice in the rock that appeared to offer a way up, a narrow notch in the granite where I was able to dig my toes into the space between the rock and the snow. I could see my friends below me on the glacier. I could also see three other climbers much further below, coming down off the glacier on the Lyell-McClure saddle. I took a photograph at this moment and in that photo you can see two of these climbers. I assumed they had just summitted Lyell and were coming down. I was wrong. Later I found out they had abandoned their ascent due to the treacherous conditions on the mountain Ė and they had crampons and ice-axes.

I turned to my crevice in the rock face and wedged my body into it. The crevice was basically a v-shaped notch with a solid rock wall on my right and a wall of hard packed snow my left. I climbed into this crack about ten or twenty feet up and soon found myself stuck. I should mention that I was wearing a day-pack, a small, lightweight back, with a water bottle (almost empty), some food, two long-sleeved shirts and the water filter. I was also holding the hiking poles wrapped around my wrists and carrying that bulky 35mm camera with a rather large lens attached. These objects made climbing difficult, as I had my chest pressed to the rock and the space I was squeezed into was narrower than the width of my shoulders. I could not climb up any further because there wee no toe holds left. My left knee was jammed against the icy snow and my arms were stretched above me, with my fingers gripping into the cracks in the rock. My hands were beginning to numb. My entire weight was on my hands and fingers and on the one left knee in the snow. I looked down from where I came and saw only the ice that lined the crevice. At this point, I think, one of my party was close enough to yell up to me. It was Doug, who had lent me the hiking poles. He was about one hundred feet below me and he was telling me to come down. Just come back down, he said. But he could not see what I could see. The ice. From below, with the glare off the glacier, itís very hard to discern the texture of the snow above you; or to your left or right. It may have appeared to Doug that coming down was a matter of simple climbing, but I had pushed my way up the crevice in inchworm fashion, using my legs and back as a sort of tire jack to rise slowly, and now I was in a spot that required constant tension, so that if I moved a leg or an arm I would slip and fall all the way back down.

I have told my own children many times: ďNever climb up into anything unless you are sure you can get back down.Ē And here I was like a treed cat. Doug asked me if I needed help but I couldnít see what he could do for me. The rock face I had just climbed was much steeper than I thought and much of the crevice was solid ice. Going back down was not an option. I had to climb up, somehow, but there was just no place to put my feet. I had both toes jammed into the crevice, one atop the other like a ballerina and they were stuck. I could not move my feet. I knew I was in a very bad spot. Because I was out of the sun, the temperature here was probably about 40 degrees and getting colder. My hands were becoming numb and club-like. If I stayed here I would only get more tired and more cold and then I would be useless. I knew that I had to climb on. Now. So I began to feel blindly above me, my hands stretched as high as they would reach. I felt around ledges and cracks and a few times I pulled loose skree down onto my head. But I found a hold somehow, somewhere, and it was a good hold.

Several weeks prior to this trip I was at a rock climbing gym in El Cerrito and I was practicing my bouldering on a sheer face not unlike the one I was on. In a few short weeks I learned how to pivot and rock and then use the momentum of this motion to catapult my body upward. In the rock climbing gym I also gained the confidence to place all my weight on my finger-tips. I was scared and I had very little strength so I asked God in that moment to give me more.

ďPlease God, help me.Ē I said. I spoke aloud. ďPlease give me strength nowĒ

I was exhausted but somehow I pulled my body up slowly. With only the tips of my fingers I pulled like I was doing a chin-up. I didnít know where I was pulling to but I just pulled and I felt something that even now I cannot explain. A surge of strength welled up inside me that felt like it came from a jolt of electricity. I still canít explain how it happened but it is the honest truth. I used every ounce of strength I had in me and even that was not enough. I needed more and I got more, I was given more. It was about 3 oíclock in the afternoon and later I will tell you why this is significant because that strength I was given in that moment was not random, it was prophesied.

In that moment, as I heaved my body up over the rock and onto a shelf, I remembered the day I caught a 175 ib. Blue Marlin in Maui. Up to this day, that was the hardest thing I had ever done with my own two hands, pulling in that big fish. I pulled myself up by my fingertips over a lip of granite and laid my chest down on the rock. I was out of immediate danger. I was out of the crevice and on top of the huge pile of boulders that make up the peak of Lyell. I laid on that granite shelf for several minutes thinking about that fish. How hard I worked to pull that magnificent animal out of the sea. It took all the strength I had and that fish, he did not want to die. He would get close to the boat and I would think, ďIím doneĒ and then he would run, and run. And Iíd pull him close again and then he would dive. And we did this dance together several times. The dance of death. And when I did pull him in I thought I won but I did not win. I lost. I lost a part of my soul, but thatís a whole other story entirely. I knew that what I was doing there on Lyell, in that crevice, was even tougher. And the fish I pulled in this time was myself.

I stood up on shaky, scraped-up legs and I looked around. I could see for miles and miles in all directions and I could see my friends on the glacier below. They were tiny black dots. The air was very still and it was incredibly quiet. I was not yet on the summit, but I was out of danger of an imminent fall.

I was exhausted and breathing was very hard. It felt as if my lungs were failing. They could, I realized, just lose their capacity to absorb oxygen. They could fail. I think if I had still been smoking I would have collapsed. At this point I had been hiking steadily for 7 hours. Climbing. Always climbing. My body felt far away and not my own. I didnít feel as if I had any control of my body. It was a surreal and somewhat psychedelic sensation. I was giddy. I could see the actual peak about 50 yards above me. I did it. I was here. I could not understand this. Why was I the only one here?

I looked around to see if there was any obvious path back down to the glacier and I could see none. I knew I had to get down before the sun dipped behind Mt. McClure. I didnít have much time. Maybe an hour. I thought that perhaps, by standing on the summit, I could see some other way down the mountain so I pressed onward. I began to hop from boulder to boulder because that is all there was up there Ė sharp, jagged boulders. It looked to me as though this peak, and the surrounding ridges, had been created in a single violent explosion.

It took me longer than I thought to reach the apex of this boulder pile. I used the climbing poles to steady myself and to catch my fall whenever I wobbled. I knew then that these poles had saved my life. When I finally sat there on the highest point, on the very peak itself, I looked out over the terrain toward the western boundary of the park. Snow capped peaks and desolation. There wasnít a soul for miles. The thought occurred to me that I was, in that moment, higher than any person in Yosemite. I was above them all. The view was spectacular and horrific. There was nothing green at all within my view. Everything was dead rock and ice. There was nowhere to go but down. A false step here would mean a long, quiet drop to an instant and complete dismemberment. A perfect death.

What struck me the most about sitting there on top was the silence. It was a muffled, suffocating vacuum of sound. Of all the things I brought back with me that day, this was the most startling and the most tangible. This was a silence you could feel in your guts. Not even my ears were ringing. It did not feel as if I was in a vast expanse of air and space, it felt, or sounded, like I was in a small room surrounded by pillows.

The sky was absolutely devoid of clouds. The sun was high above my left shoulder, and I was closer to it than I had been since I had sat in this very spot as a 24-year-old boy. Everything was clear, sharp, but it felt like it was in 2D. It felt painted and flat. I could not really discern distances or the edges of things. Perspective flattened and I could not judge accurately the relative depth of objects or their relationship to each other. On top of that mountain I was trapped inside a funhouse mirror where things got smaller one second and taller the next.

I knew I didnít have much time. I took out my camera and snapped off a few shots and then I turned on the video. I took a panoramic 360 degree shot and then turned the camera on myself. I regret now that I did not say more than I said in that moment. I am disappointed in my deathbed confession. I did record a message to those whom I thought might find my corpse, but I did not go far enough in taking responsibility for my actions and I neglected to say any last words to the ones I love. What I did record was a frank and sincere assessment of my situation and my errors. I made a foolish mistake attempting this climb and time was now my enemy. Getting up was one thing, getting back down would be a an ordeal of another kind.

I had to get moving. The vantage point I now stood upon offered me no other route back down. I could see no better path, no comforting alternative than to go back the way I came. I climbed down to the spot where I had climbed up earlier and I saw my friends at the base of the glacier. They were so small and far away that I had to squint to see them. I could not see over the ledge in any direction and I became terrified once more. Without knowing where to descend, I feared that I could easily find myself trapped on a precarious ledge with no way up or down. What I needed was a guide. If someone could stand below me on the glacier, I thought, they could direct me to a safe route, because the only way down was for me to crawl backward, as if I was climbing down a ladder, feeling along the rock with my feet for purchase and support. I needed help.

It was humiliating to admit it but I was beginning to feel that dread sense of panic welling up from that primitive core where instinct still holds sway over intellect. I remember a period of about two or three minutes where I was literally pacing back and forth in confusion like a dog trapped on an ice floe. In a crisis there are always key decision points where later on you realize your life hinged upon your will to act, or not. I had already made one such decision when I pushed on up through the crevice. Now I faced my second, and perhaps most dire decision node. In a flash I saw myself huddled up here on the rock in the dark with the winds howling and the temperature somewhere in the 10-15 degree range (the night before some hikers we passed reported that it dipped to 16 degrees on Vogelsang Peak, so it was not a stretch to consider it dipping even lower at a much higher elevation). I had a long sleeved shirt and a thin fleece in my backpack but I was in shorts and had no water. Could I survive the night? Maybe. It was then I remembered the Himalayan climber Beck Weathers.

Beck survived much worse conditions in a howling snowstorm on Mt. Everest. He was left for dead, bare-chested in the snow, and he survived. He lost his hands and feet and a good part of his face but he lived, so I thought I would likely live, through a night on the mountain, but at what cost? I did not want to find out. I am not a person who sits still and waits for things to happen. I needed to get down but I was scared. I was gripped by crippling fear.

I walked to the edge and looked over and then I did something I had never done in my life. I called for help. I screamed as loud as I could and it sounded strange coming out my mouth. Help. This was the first time literally called for help. I shouted. I cupped my two hands around my mouth and bellowed. Help. My friends heard me but they didnít do anything. They didnít move. I could barely hear them call back. All I could make out was them telling me to hang on. Hang on? Hang on for what? Then I shouted back, S-O-S. Help. Help. Help. All I got in return was, ďCome on Vin, you can do it.Ē I wished to God we had those radios, because I wanted to curse a blue streak.

Thatís when I knew that nobody was going to come help me. I even imagined the helicopter that theyíd send for me, but such an image was embarrassing. I didnít want to be rescued that way. I didnít want to be rescued at all. I was still able to walk and climb and I was not going to give up. So I prayed. I prayed aloud to God and I asked him to get me down from here safely. I told him to do his will with me. Kill me or save me. Whatever would happen when I went over the edge was all right with me. As Sitting Bull said, it was a good day to die.

At this moment I was angry. My friends, I thought, had abandoned me. I called for help and they did not come. These are guys who I have known since high school. In my mind, at that moment, I thought, here I am, in trouble, in danger, in need, and they put themselves first. I was angry and indignant. I resented them. I wanted to yell at them and shame them. And maybe this was a good thing because my rage became stronger than my fear. Sometimes anger can work for you. If properly channeled it can act like rocket fuel. And I needed this. I would discover later that the anger was ridiculous and misplaced, but for the moment it was necessary and welcome. I needed to get down to that glacier and I needed to overcome my terror, and my anger came at the right time for me to make what turned out to be a very crucial decision.

I packed my camera into my backpack and shortened the hiking poles so that they would not be an encumbrance to me. I remembered that ever since I was a little boy I had loved climbing rocks and that I spent a good deal of my childhood doing that. I was good on rocks. I was always a good climber. Why shouldnít I trust that now? Then I prayed once more and went over the side like it was the most natural thing in the world, like I was in the rock climbing gym. And I just climbed down.

I made my way down the rock face one careful step at a time, feeling along the rock with my toes, testing each ledge, shifting my weight to test each hold. After several minutes I was standing once again on the lip of the glacier. I was off the rocks but I was about 25 yards from the spot I had been in before. And now, to my horror, I was standing on solid ice. The lip of the glacier where it met the stone had been worn smooth by melting water and I could not move for fear of sliding all the way down.

The glacier at my feet dropped steeply and there was before me a crevasse that was about 20 feet long and maybe 3 feet across at its widest point. The entire crevasse was solid, clear, almost blue ice and it was filled with ice stalagmites that rose from the depths of it like daggers. I realized that I was been climbing above this crevasse only moments before. If I had fallen, my body would have been wedged tightly into what amounted to a mouth full of glass spikes. Even now I was dangerously close to this beautiful, horrific hole. I had to work my way around it and I did so by squatting and digging out foothold with the tips of my hiking poles. I lengthened the downhill pole to act as a brace and left the uphill pole short to use as an axe. As I crept past the crevasse I could feel the mass of freezing air that was inside of it like some pocket of noxious gas. I thought for a moment about taking a photograph of this remarkable sight, but my camera was packed away on my back and to take it out would mean a dangerous shifting of weight and a momentary abandonment of my hiking poles. The mere sight of that deep gash in the glacier erased what confidence I managed to regain after coming down off the rocks. I had jumped out of the frying pan into another frying pan.

The mountain was steep here and the glacier was frozen into hundreds, no thousands, of brittle, icy scales, some as deep as a bathtub and half filled with slushy water. There was no space between them, no place to put my feet. I had to walk through them or slide into them on my rear end. I took one tentative step and instantly lost my footing. I fell and I slid. I slid down several yards, gashing my elbows, cutting open my knees, losing one of the hiking poles and bumping down the hard, cold, wet ice on my coccyx bone. I only stopped sliding because I slammed into the frozen underside of one of the ice scales. I was wracked in pain and when I stood I watched bright spots blood dripping steadily onto the ice. It was my blood and it was dripping from a wound on my knee. Now I knew what the awful possibility might be should I slip and fall. A long tumble forward, end over end, bumping off of jagged ice blades, ripping and tearing my skin. A foot misplaced meant a fall of hundreds of yards.

I sat in the ice water. My shoes were soaked through to the skin. My left elbow was gashed up to the wrist. One of my hiking poles was 10 feet above me and out of reach. I thought I would leave it, as earlier Doug had said it would be ok if I were to lose the poles. But I still had a long way ahead of me and I needed both poles to get me across this glacier Ė which had now been melting for several hours. The entire surface of the glacier had changed texture since I had crossed it maybe an hour ago. It was wet and icy and treacherous. I needed that other pole. So I crawled back up to where I had fallen and I used my remaining pole to poke and than skewer the wrist strap of the one above me. I pulled it down. Now I could push myself up to a stand, and it required all my strength to do that. I was a wet, throbbing, bloody mess but now I could see one of my friends below. I had not been totally abandoned. Robert was standing there, about 300 yards below me. And I knew he would have water. And I knew I would not be walking back alone to camp in the dark. And I knew I would make it.

The rest of the way down the glacier amounted to me falling, sliding, slipping and stumbling through the jagged snow cups. My legs were so wobbly that they would just slip out from under me and Iíd fall with almost every step. But I did it. I got down across the glacier and met Robert where the talus field began. He didnít say a word. He threw his arms around me and pulled me in for a hug. At first I did not want to hug him back. For a moment I wanted to say fuck you. I wanted to deck him. But something changed and it changed very quickly. My anger drained. It was just gone. I loved him more than I ever did for just being there. I was grateful I was not alone. He had water and I drank a full pint in one long swallow. We didnít speak. I didnít say a word. I couldnít. I took out my camera and snapped a few photos. He took the camera and snapped some of me, bleeding, battered, but otherwise whole. I was alive. We had 10 miles to go and it would be a long and grueling walk to camp, but weíd make it.

The walk down from Lyell Canyon is a blur to me. We crossed a mile of talus in a daze. Huge boulders that had crumbled and fell from the cliffs above. Thousands and thousands of rocks. My knees. I could not comprehend how they could hold me erect, let alone plant, pivot and push. The sun had dipped behind Mt. McClure and I could see the notch in the rock where I had been trapped earlier. The mountain was cloaked in shade. The shadow of the mountain was moving through the canyon. Our own shadows were 30 feet long. We looked like a couple of stilt-men in the golden light. All I could hear was Robís breathing and my own breathing. I was breathing. I had lungs. I was aware of my body as a thousand points of light. My body was a thing I inhabited like a house. I was the tired pilot of my body. My body was the avatar of my soul. I could, if I wanted, leave my body and hover above it. It wasnít even mine, this body. My flesh and my blood and my bones. My body was a provisional refuge. An old glove, a beat up car, a good boot. I know there is a soul. I know that the body comes from dust.

We walked in silence, Robert and I. We got back well after dark. My other friends, Phil, Mike and Doug had only arrived 15 minutes before we did, so we made incredible time, considering they had a head start of over an hour. It was very cold and as soon as I sat near the fire I began to shiver uncontrollably. My arms were shaking so severely that I could not hold a cup. I was not hungry. I did not want to talk and I did not want to eat. I did not want to look at anyone. I was filthy and bloody and I did not want to wash. I wanted to sleep. I put on all the clothing I had and crawled into my sleeping bag but sleep did not come. My body, that strange cocoon I know longer knew, wanted sleep, needed it, but my mind did not, could not possibly sleep. My mind. I laid in my sleeping bag for hours, not thinking, but receiving. Images, sensations, words, faces. I saw my grandfatherís face. I heard his voice speaking to me. A man who was killed long before I was born.

What I thought about there in the warmth of my sleeping bag was this: Nobody was responsible for my predicament. Nobody abandoned me, I abandoned myself. I made several critical blunders. I was wholly unprepared. I was more than foolish, I was stupid, careless, reckless. I could have been killed. I was also arrogant. The whole trip was an exercise in arrogance.

It is very easy to ignore the dangers in the wild. Yosemite is a beautiful faÁade. Trees and rocks and sky are pretty things that can lull us into a false sense of security. Gear guarantees nothing. When you walk out into the woods you put yourself into the hands of something that runs by its own rules. And we are fragile. We are as delicate as a wildflower. But I think itís necessary, these pilgrimages we take. Because we need to remember who we are Ė nothing. 9/11 taught me that all the sheet rock and concrete and steel girders man can engineer can be reduced to a cloud of dust in minutes. We are nothing. We are flesh and bone camped out on a planet of fire and water and rock.

Twenty days later I am still trying to understand what this trip to Yosemite means. It seems that every time I go thereís a lesson waiting for me. Itís always that way in the wild. The wild reminds me that I am flawed. The woods remind me that my life is fleeting and, ultimately, insignificant. But I am also stronger than I give myself credit for. And there are no heroes. Many people love me, a few believe in me. But only I can save myself.

[If you wish to watch the 8 minute photo essay of my trip to Yosemite, follow the link in the upper right of this page, at the top of the blog. It's called Yosemite Movie.]

[ view entry ] ( 7238 views ) | permalink | related link |

( 2.9 / 710 )

( 2.9 / 710 )I want to tell you about something that happened this Sunday past. I had myself a day of strange encounters with animals. I want to tell you about one of them.

I was on a deserted beach at Point Reyes. I hiked in two miles from the road and had just emerged from the dunes. I stood before the roaring ocean and a fierce onshore wind. I looked to my left and saw some interesting flotsam, mostly washed up trees. I looked to my right and saw nothing but blowing sand. Which way would I go? I didnít know.

Then something caught my eye to my right. I could see it as a blaze of glaring white, a glowing spot on the sand. There were ravens circling above it. Thatís how I discovered it, I followed the ravens. I saw the ravens long before I saw what they were after. They flew right past me, just above me, and flying into a terrific headwind. If I had wanted I could have reached up and plucked them out of the air, they were that low. Where there are ravens going I almost always follow.

I wanted to know what the ravens had found because they are keen-eyed birds drawn to the curious; as humans are. The wind was blowing a good 20 knots off the ocean and the air was a storm of flying sand. I could hardly see without my arm there before my eyes to shield them.

I could see the ravens now as black specs, wheeling above a spot on the sand a thousand yards away where it seemed a star had fallen, an object of great brilliance. I saw there were vultures too. This was awhile back. I spotted the vultures before I spotted the ravens so I knew there was a carcass somewhere, and on such a lonely beach as this one I knew it had to be a seal. But now there was a white thing on the beach and beside the white thing was a black thing and I knew what that was. I didnít know what the white thing might be but as I drew closer I understood it was a bird, but I had never seen a bird like this before. There was something strange about it. The shape. of it. And it was so white it hurt my eyes to see.

The ravens were pecking at the bird; which I took for dead but when I got close I could see it wasnít so. The bird lived. I shooed the ravens off but they did not yield right away so I spoke to them in that voice you take on when you talk seriously to a dog who forgets his place and has to be reminded whoís boss. The ravens heeded that tone and they flew off but not too far, for like I said theyíre curious creatures and they wanted to see what I would do.

When I turned I saw the whiteness for what it was, a herring gull, and about the whitest Iíve ever seen. It was on its back and both of its wings were bent back and folded under it in a manner that was almost funny. The wind was incredibly strong off the sea and I figured the bird got knocked down by it and flipped over somehow. He was all tangled up in himself and about as flummoxed as an upside-down tortoise. I didnít understand why he couldnít right himself but I waited to see what he would do now that the ravens were gone. He flapped around pathetically. Broken wing for sure. So I went up to the high water line and found myself a long stick. When I got close I could smell the seal carcass, it was a big one, and it had been picked almost clean to the bones by the birds. The gull panicked when I got near him and it tried to scurry but it was no use, it could hardly move but in a circle, using its one good wing as sort of an oar in the soft sand. It was doomed. I donít know why I didnít take out my camera. It would have been an interesting shot. But I didnít. Instead, I soothed the bird with another kind of voice I used to use on the dog. I whispered to him and told him I wouldnít hurt him and I approached real slow and got down beside him and flipped him over neatly with the end of my stick. He popped up and waddled off and then he tried to fly but the wind was too strong and he was grounded. He kept leaping into the air, as was his right, but the wind and his wing would not give him his privilege. The bird could not fly.

Later on I found him in the dunes. He was hunkered in the lee of a small mound of grass. One of his wings hung down oddly at his side. I wondered if he would live through the night. I had seen plenty of coyote sign on the long hike in to Abbottís Lagoon and I figured they hunted the high water line of the beach at night for carrion. Maybe this big white bird would make it. I donít know. For the moment it was safe from the terrible beaks of the ravens. As much as I love and respect those black birds it is the free-wheeling gull I think I admire even more. I came of age in the 1970ís when a certain little book about a seagull sat on my motherís coffee table and captured my imagination. I can still see the cover in my mindís eye. I see a bird in flight, soaring, with its wings outstretched. The silhouette is glaring white. I never did read it but I know what itís all about. That book, and that image is tattooed on my mindís eye.

I believe that there are no such things as accidents. I arrived on that beach last Sunday morning as if borne by a magic carpet. Call me a fool, but I believe in signs and omens and the spirits of the dead. I believe that animals can talk to men and that trees have souls and that the earth can grow a certain flower for the pleasure of my eyes alone. What I find on my path was placed there by forces I donít need to understand. This life can be a wonder and a terror both, but mostly it is a wonder.

One thing I did that morning was to crawl around on my hands and knees on that beach, to pick out the tiny polished stones exposed by the blowing sand. They were shiny like the eyes of a bird and and I found them in all varieties of color, most of them no larger than the nail of my thumb. I filled my pockets with pebbles, as smooth as if they came right out of a rock tumbler. I like to think about the age of rocks and how far theyíve travelled. I like the way certain stones feel in the palm of my hand. I like that no two are alike. But I think what I like most about finding buried stones is that most likely I am the only human being to have ever held them and then, if I hurl them into a pond or take them back home for my collections, the only one who ever will.

The herring gull whose life intersected with my own that morning was watching me as I did this. He kept his distance as I picked through the stones, and I found myself talking to him, telling him heíd be alright if he just rested awhile and that I wasnít going to hurt him - the kinds of things a child might say to a stray dog. I donít know why Iím telling you all this. I donít know what it means. Probably nothing at all. Probably we look for meaning in personal incidents and unexplained events because we need to feel like thereís a reason for our confusion, for our living and for our being. Maybe I am the most primitive kind of man. The older I get the more childlike I become. I want to believe there are no coincidences. I have to. I know from first hand experience that there are forces at work beyond what we experience with our senses and with our rational minds.

Every time I go to the beach I arrive home with a pocket full of shells and stones. Little shards of glass polished by the action of sand and wave. Small pieces of wood worn smooth and streamlined. Bone, bleached by sun and rain. Why do I take these things? Why do I treasure them? Why does the seagull matter?

A truly singular, individual experience is rare in 2010. Today, everything is shared. But to be alone and to touch the universe is something that cannot be Facebooked, text messaged or Twittered. A connection with the infinite just does not convey. And I want that again. I yearn to see and think and feel what *I* feel and to derive meaning and affirmation in my own way and on my own time. I no longer want instant anything. My mind has been neutered and my soul cheated. Of true experience. In real time. In no time. And alone, or with one good friend whose face I can see off the page of some remote electronic book.

The seagull was real. The carcass of the sea lion was real. The ravens were real. The blowing sand was real. This is magic. Sand, wind, life, death, tides. This is magic. Now I know why I left Facebook. And if youíre reading this, so do you.

Thank you Jonathan Livingston Seagull.

VC

[ view entry ] ( 12533 views ) | permalink |

( 3 / 5683 )

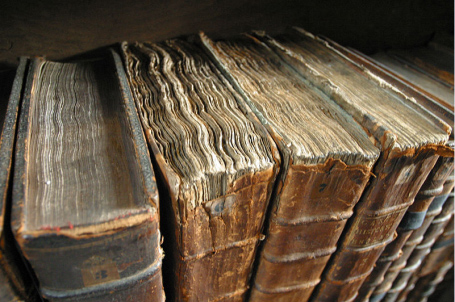

( 3 / 5683 )The novel is the only thing that really matters to me. The book. It's the only thing that makes a difference, the only thing that makes a lasting dent. A novel burrows and inhabits. It's a thing I can hold in my hands. Pages. Text printed on paper. To see the whole before it is consumed. That's another thing that sets it apart. To see it. To feel its weight and measure its thicknesses.

Books do things to me. Like nature. Like weather. They surprise me by showing me myself in new but familiar forms. The novel, the right novel already exists in my head before I ever open it. It's just been waiting for me. The books that I read and the books that I hope to write are patiently waiting, Reading them, or writing them, simply reveals the details of what I already seem to know but have not yet articulated.

A novel is a miracle. Born in another time within another human's heart, a stranger's heart , unfolds inside my own, in my present. A single human being enters another. Intimacy without knowing. A faceless form of love. A code exchanged across space and time wakens neurons, fires, neurons, creates images, feelings - good God, the feeling of it, the way a book makes you feel. That subtle tickle in the back of the lower part of your throat, like a contraction, the choking part of 'choking-up', the waves and the vibrations, the rising joys, the shivers of revelation, how your body just hums, sometimes, how it physically reacts to sudden and unexpected understandings, recognitions of something lost and buried being slowly revealed. A film does not do this. Not as personally, not as intimately. A painting does not do this. You have to work harder to see yourself in a painting. But novels seep into all my crevices. A novel is a liquid that fills the empty spaces and conforms to the shape of its container. The container is myself.

In a sense a book is a container and a story is water being poured from one vessel into another. From one body into another. A book is a bottomless vessel. One copy of To Kill a Mockingbird can fill a million little cups across ages. Is a writer then a bartender? A chef? A chemist? No, an alchemist, transmuting souls. Great novels transmute me, transform me, transcend me. There is nothing else like a novel. The only other art form that comes close is the song. Music does this. But I cannot write music so I write words. A paragraph is a song. Great novels sing. They well up like Negro spirituals. I can feel them in my bowels, in my bones. They get inside me because they come from inside me. I am always the focal character. I am Madame Bovary and Holden Caulfield. This is not a simile. I am not like them. I am them. This is what really separates novels from movies, from music. I never feel that I become the person on film. There's always a separation, a wall. I don't see me there and I don't feel me there. I may have empathy and sympathy but I am never them. We never blend. But in a book I am that person, and sometimes many people. This is occurring at a subconscious level. We are contained within the container. We hold ourselves in our own hands. We are connected.

I need to carry my books wherever I go. I want them to get wet and dirty and bent and scuffed. When I am finished I want them to know that they've been read. I like my books like I like my people - beaten and worn. Damaged. There's no such thing as a digital book. Words can be digitized, books cannot. A book is more than words. Books have souls. Even different copies of the same book are unique.

If story does not occupy physical space, if it does not have volume and texture and smell and a sound then I find that it is lacking something vital. A cover; which is a door. A title page; which is a curtain. A typeface; which is a secrete code through which I absorb and discover, a certain paper stock - the emulsified pulp of living things, a tree. A book is a resurrection. There is poetry in this that justifies the death of the tree.

I know trees. Trees will willingly give their lives for great books. It is an honor to them. Whole groves should be grown specifically for this purpose. I see now in my mind's eye, an eye created by 40 years of reading, a father planting an orchard at the birth of his son, who will grow up to write a great novel to be printed on the very paper milled from that grove. I see that boy wandering his orchard, touching his sacrificial trees, speaking to them, whispering to them like a toreador worshiping his bulls. The sound that the wind makes in their branches is a language only he can understand. The power and magic that is contained in real books originates in trees. Trees are the elusive philosopher's stone in this mystery equation. It takes a tree to make a book. For a book to have its power lives must be lost.

Novels grow on paper like fungus grows on the bark of dying oaks. New life is fertilized with corpses. Every book should be a resurrection. And that is what I feel when I hold a real book, a great book, like Shadow of the Wind or Cold Mountain, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, The Sun Also Rises. Something died to bring those stories to me, and I must feel the weight of those deaths and treasure them, like the mummies of the pharaohs. I must worship them, dust them, keep them clean, open them from time to time to read random passages. Every great book is a funeral and a celebration.

[ view entry ] ( 6542 views ) | permalink |

( 3 / 5705 )

( 3 / 5705 )I apologize to Shelby Lee Adams for posting his photograph, Boy with Serpent Box and Poison Jar, without his permission. Copyright is the only protection an artist has and it should be taken seriously. I did not do that. I wish to express my regret for this oversight. It was not my intention to offend the subject in this photograph nor to exploit Mr. Adams.

I will be taking down the photograph in question as soon as I can contact my webmaster. I have already removed another copy of it from my blog on which I included a caption which the subject may have found offensive. For that I am also sorry.

I tried to write Serpent Box with respect and dignity toward the Pentecostal movement that inspired it. I have tried to portray Holiness people as God-loving, spiritual human beings. I have heard from several Holiness people who have read the novel, and they have told me that I did in fact succeed in doing so. But Serpent Box is a work of fiction. It is not based on any real people, and is not meant to be a documentary about snake handlers. That being said, I was moved by Mr. Adams' photos. His incredible book, Appalachian Portraits (which was ironically stolen from me) introduced me to these people, whose faith in God and Jesus infected me, and provided me with the impetus to re-discover God in my own life. I am truly grateful to him and to his subjects.

It has also been brought to my attention that certain photographs on the site should be credited to Russell Lee with appropriate copyrights attributed to him. These I got from the National Archives and at the time did not see such a credit nor was I aware of the Commons Licensing requirements. This will be corrected shortly.

[ view entry ] ( 3884 views ) | permalink |

( 3 / 5663 )

( 3 / 5663 )

Random Entry

Random Entry