http://www.silive.com/siadvance/stories ... amp;coll=1

I won't re-post it here, but if you're interested please check it out.

VLC

[ view entry ] ( 8042 views ) | permalink | related link |

( 3 / 5302 )

( 3 / 5302 )And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you”

There was a lake nearby where we took the canoe early that first morning about two hours after the passing of a storm in the night. The water was flat and clear as resin and we were the only anglers upon it, just my brother and myself, as we had done countless times in our boyhood, only then in our father’s old canoe. The air about the lake was muggy and bore a weight I had not felt in many a year. An Eastern summer. We paddled the canoe in a silence broken only by the sound of the oars as they rose and dripped and I could feel inside myself a certain shift. Something was happening, triggered perhaps by the closeness of heavy air and fecund lakefront and insect-sound and heat.

We skirted the shoreline with our poles rigged, watching for fish-sign, and flushing out the hunting waterfowl in our silent passing. There were herons of green and blue and white, and mallard duck and Canada goose and Belted Kingfishers and low-skimming swallows that nested in mud-holes beneath a low bridge we ducked under as we made for the shallows beyond to acres of lily-pads in bloom. The air alive with bullfrog calls and cicada drone. That’s what it was, the cicadas. A neural switch thrown in the circuitry of memory and heart. Sound and smell and scene. The willows bending low over the lake, their leafy tresses dipping, trailing. Maples and Chestnut oaks filled with the sound of cicadas calling to each from a thousand hidden places, sometimes with their slow clicks, sometimes in a consistent alien buzz. The sound-scape was as omnipotent as the heat.

For all the glory of the East in summer resides in the annual return of these primeval things. Coal-black with emerald trim. As big as a man’s thumb. Their caviar eyes alien and aglow, a trilobite with wings. Their sound is a summer song as sweet as birdcall, and to my mind sweeter. A distant ticking. A staccato hum. You hear it everywhere at once. A surreal warble that seems to rise and fall, rise and fade, it is a sound that permeates my heart. It sends me back to a time of mystery. The days of smallness and wonder. I cannot think upon my youth and not hear them, aloft in the Sycamores. Cicada. The rhythm of the heat.

Here’s what I knew. I had three readings in four days and one book club appearance. I spent the first night in New Jersey, the second in Brooklyn the final two in Staten Island. I foolishly rented a car. After getting lost the first day and stuck in midtown Manhattan traffic for three hours I cursed the machine and the terrible roads it traveled. Driving in New York is a bad-crazy dream.

I spent that first morning on the lake with my brother, as recounted above, and it set the tone for what became a spiritual journey akin to a pilgrimage. As I said, something inside me shifted. Something inside me awoke on the lake. Old clusters of neurons. A network of images and emotions triggered by sense – my skin, my sight, my ears, my nose. The human brain is endlessly marvelous. Nothing that enters is ever lost.

My subsequent trip to Manhattan all but sapped the joy out of me. I got lost. I became flustered. I missed a very important meeting with my editor, whom I had never met. I became angry and I could feel the all the venom return that I had left behind twenty years before when I forsook New York for California. The poisonous dread of manic energy and callousness. The fear. There is something about New York that is anathema to my soul. Yet, there also something there that has the power to heal me.

I missed the meeting with my editor, but I did make it to my very first book club appearance; which convened at a lounge on 96th and Broadway called Unwined. The club’s organizer is a friend of a friend named Jordana, and upon meeting her all the bad mojo of the previous three hours ebbed away. Warm, welcoming, sweet, Jordana exuded a brightness that melted the thin crust that had begun to harden again around my old New York heart.

The book club has no name that I’m aware of, but since most of the women involved know each other from working for Sesame Street (the very program that taught me to read) I am dubbing them the Sesame Street Readers. And they were wonderful to me. They didn’t just read Serpent Box, they absorbed it, they lived it. They knew more about Serpent Box than I did and saw more in it than I had ever conceived. They understood the characters and they understood its themes. These women were students of books. Their questions were thought-provoking. Their kindness humbling, and their praises a blessing.

We spent over two hours together. I answered their questions and I read to them – something I was told they’d not asked a guest author to do before. We shared the story together as lovers of story, as lovers of words. For the very first time I understood that I was not the one for which Serpent Box was written. The book no longer belongs to me.

[16] I resist anything better than my own diversity,

And breathe the air and leave plenty after me,

And am not stuck up and am in my place.

I slept that night in Brooklyn at the home of the person who started me on my path to writing, Jonny Belt, who was the spark for Serpent Box. Something about spending an evening with him, and his one-year-old son Grady, was grounding and necessary. Jonny was the first person to see me as a writer and as we wandered the quiet streets of Carroll Gardens early that Thursday morning with little Grady in his stroller, the trees filled with cicada-din, I felt the visceral pull of return, of resurrection. I said to Jonny, This is unreal. The sound of the cicadas. You are so lucky to have them. Jonny looked up at the trees above us. He listened. You know, he said, I don’t even notice it.

My first reading was at Barnes and Noble in Manhasset. But that was not until 7 o’clock, so I had the day to myself and the question I faced was, what do I do? Spend it in Manhattan? The mere thought of driving back into that city filled me with dread. So, on a whim I decide to drive to the Long Island town of Port Washington to visit my boyhood home. As it turned out, this was a momentous decision.

It had been more than twenty years since I stood before the shabby little house. The same mustard siding. The same stunted shrubs. And as I gazed upon it on that humid Thursday morning, with the cicadas clacking away lazily in the old sycamores, I shrank. I became a boy. I was struck with a profound sense of time and place, and overcome with both melancholy and joy. I traveled back in emotional time. I felt I could just walk up the driveway and enter with my hidden key and go to my old room and lay down to bed.

I wandered around the house and took some photographs and then I walked the block itself to see the homes of my old friends and those secret places where we had gathered to smoke our first cigarettes and spin the bottle and hunt out toads and snakes. I got back into my rental car and drove the neighborhood. A map of my old living, my first life. I went back to by elementary school and walked through its halls until I found room 20 where spent the sixth grade with the one teacher who had somehow reached me, a man named Walter Chaskel. I could see the ghost of him framed in the doorway. Inside, the same light, the same smell – book glue and floor polish.

I spent the morning in the car I had cursed, following the trails of my heart’s creation. I drove to places where I was beaten in fights and where I had fished and sailed boats and I ran my old paper-route exact, noting who had tipped me and who had not, and I sat the Toyota at the curbsides where the homes of my old friends still stood bearing their exact impressions and all wrapped in the quiet of a still summer day as if sealed in amber, bewildered at my return.

I turned the car toward the Long Island Expressway. I had known that Walt Whitman was born in the town of Huntington, where his first home was preserved, and that there was an exit for this place, so there I headed and ran headlong into the most intense thunderstorm of my existence. The traffic on the L.I.E. ground to halt as a charcoal tail began to form at the base of an enormous thunderhead twelve o’clock high not five miles before me. First the rain fell, and it was blinding. I counted fifty air-to-ground lightning strikes before the hail flew. The sound of the hail on the roof, on the hood. A storm of gravel, a storm of Bird’s Eye peas, like some broken snare drum beaten by a madman. Cars pulled off to the shoulder and other stalled but I pressed the Toyota on and found the exit and found the tiny road-side signs that directed me to the house. I pulled into the empty parking lot as the rain began its slackening. I was alone.

The old docent was stunned at my appearance in such a storm but he showed me the small museum and played for me the only known recording of Walt’s voice, faint and crackling, and transferred from a wax Edison cylinder so that it sounded ghostly, a line or two from Captain O’Captain. The old docent whose name was Harold bade me to sit and watch a short film until the rain stopped. I did this. Whitman’s own voice. Good God I can still hear it. When the rain did stop Harold escorted me to the house. We stood in the colonial kitchen where he took his meals, and in the room where he had slept and I asked to be alone for a moment in the room where he was born. Again, there was transference. Planets were aligning. Had aligned. Walt was in me. As I emerged into the sunlight beside the old well, the cicadas began to click.

Later that evening I read for a small gathering of friends and loved ones at the Barnes & Noble in Manhasset; the town where I was born. I read from my own novel, my creation, yet I was struck by a passage that was clearly inspired by Song of Myself, and I stopped at that moment and looked up at my little audience and made sure they knew it too. Right there, I said, that’s Whitman. And my voice cracked, because I knew that what I had written was not my story, but all stories, and that in order to write it I had stood upon the shoulders of Walt and Ernest and Dylan and Tom Waits and Cormac McCarthy and Rumi. So many more.

If my journey had ended that very night I could well count it as a great blessing, if not catharsis. But I had two more readings to go. The next was at the Port Washington Public Library – the place where I basically learned to read as a boy. The reading was at noon on Friday – 8/8/08. What I thought was that a small group of old friends would show up and I’d read for them in a tiny corner someplace. I did not expect sixty plus total strangers in a large auditorium and a college English professor as an emcee. I was stunned. The room was packed. The gentleman who met me onstage not only introduced me, he interviewed me. He had read the book and was well-prepared. He even read passages himself. It was incredible. The discussion was lively and fascinating. Why did you write this book? Did you go to Tennessee? Are you religious? Why was Jacob deformed? Why introduce Hosea so late? How do you learn dialect? Why did you decide not to use quotation marks? And then a hand went up and a man stood. He was elderly but familiar. I knew that face. He said, “Vincent, I don’t have a question, I have a comment. I am proud of you.” My God, it was Walter Chaskel, my sixth grade teacher.

For years I searched for him. Every so often I’d Google his name in hopes of finding him, reconnecting with him. He was the best teacher I ever had and I simply wanted to tell him that he mattered, that he reached me, that he had an impact on my life. He was the kind of teacher that placed life-experience above academics. He introduced me to great places and great books, and he read to us, every day, in a voice that would lull me into a sleepy bliss. And suddenly there he was, sitting right in front of me in the audience.

About two months ago one of my Google searches turned up a hit. I found his name in an article in the New York Times and tracked him down through it and we had exchanged several emails leading up to my trip to New York. Having him there at this of all readings was about as fulfilling a feeling I have ever had. The student reading his own book back to the teacher who opened his eyes to the power of stories.

[20] And I know that I am solid and sound,

To me the converging objects of the universe

perpetually flow,

All are written to me, and I must get what the writing

means.

Serpent Box has become for me (and perhaps it always was) a bridge. Not back to a former self, but to a self that was always there. Hidden. I am everything I ever was. I am the moment and the memory. Carlos Castaneda, in the Eagle’s Gift, describes the essence of the self as a luminous egg-like light with an infinite number of tendrils that connect us to all things. I felt that light in Port Washington. Serpent Box has helped me to glow.

My final reading on this mini book tour was not set in a house of books or a house of learning but in a house. My mother wanted to do something for me in recognition of the Serpent Box’s release and she graciously set up and event at her own home on Staten Island. It was a catered affair that took place in her lovely backyard, and included relatives and old friends and most of the people that mattered to her, so I felt more anxiety than I normally would before a reading. When I read at a bookstore I am standing in front of book-lovers. An avid reader is always prepared for a journey of the heart and imagination and I am confident enough now in Serpent Box. I know I can hook you. I know I can suck you into its world and make you see what I see and believe what I believe. But in my mother’s backyard were not the typical readers I encounter. Many (as they confessed to me later) never read at all. So I was more nervous than usual when I was introduced to this rather raucous crowd who had been drinking, and reconnecting with each other that afternoon by telling their own stories in their high-volume, high-energy New York manner. New Yorkers are story-tellers and good ones. The oral tradition is alive and well in the East. Could I enthrall them? Could I capture these tough New York hearts with a story of a boy set in the South? I didn’t know for sure, but I had an idea. I would read an excerpt designed to convert unbelievers.

Chapter 15 of Serpent Box is called Slaughter Mountain, and it recounts a tent revival where identical twin preachers attempt to handle a wild African Cobra before a large congregation of the faithful. It is a fire and brimstone affair designed to arrest the attention of the faithless and bolster the hearts of believers. It is one of my favorite chapters to read aloud. I read it that afternoon with the fervor of a prophet, and when I stopped reading the crowd sat in stunned silence. I had moved them. I could see this by the looks on their faces. My fictional sermon broke through. I brought them to me through a story I wrote in the weakest moment of my life. How could I not be humbled by this?

Later on that evening after the guests had departed and as we were cleaning the deck I was on my hands and knees with a dust pan and broom trying to sweep up behind a potted plant when I found something I had not seen in many years. I recognized it immediately. It was the husk of an insect. An amber, translucent shell about the size of a peanut with two bulbous eyes, six jagged legs and a slit up the middle where the adult had cracked itself out of its larval form. A cicada. You find these on the trunks of trees and on fence posts. I used to collect them when I was a boy. They’re quite fragile and a little frightening, like something H.R. Geiger might conjure from a dream. I carefully stowed the husk in my luggage and brought it home.

[31] I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journeywork of the stars.

On the lake that morning we hardly spoke. There is no need to speak between us, for everything that could be said has been spoken. The language of brothers is in the eyes and in the heart. There is a stillness in this. A quiet joy. Try the reed bed over there, I might have said. Let’s see what we can find beneath that fallen willow. Those were the hours I traveled for. Alone on the lake with the one who knows me as I know myself.

If you spend any time at all on the water you know the feeling of fish. You can sense them. You become attuned to the conditions under which they rise and feed. The lake that morning was pregnant with living. We saw the fish. We saw them dart and we saw them jump and we felt them hit our spinners and our jigs. Moments after the rain, as insects fall from the trees, as worms and grubs wash in with the runoff, the time is ripe for fish. But alas, we caught nothing. And it was no matter, that. For fishing is not about catching. Fishing is being close to home. Fishing is listening, and watching, and absorbing that which we have lost – a certain union with the mystery. We are of the water, we are of the grass.

[52] I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love.

If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles.

All quotes are from Song of Myself, Walt Whitman

[ view entry ] ( 9247 views ) | permalink |

( 3 / 3641 )

( 3 / 3641 )

The Birds

“We all know we’re going to die; what’s important is the kind of men and women we are in the face of this.” Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird

The thing was, I thought I might never write again. This was a month ago. I was all but defeated and I lost my faith, not because of the writer’s block or the endless rejections or because I was not published. I lost my heart because I was published. It was the publication process specifically. That cold, reality that hits you like a cancer diagnosis.

It sets in about a month after the book hits the shelf. There are a few reviews, a handful of readings and some brief mentions in the press. And then suddenly it stops. It gets very quiet. Bookstores don’t let you read because you “don’t draw”. Your publisher doesn’t want to allocate any marketing dollars because you’ve not “caught fire”, and you are told by your peers and your agent and your editor alike that the success of your book is on your shoulders now.

It’s just not enough to struggle for years to create something real and true and from your heart. It’s not enough to endure the process of finding an agent, of selling a novel, of preparing it for publication. That trail of tears is only the beginning. For when you arrive, the great rock that is your heart’s creation rolls back down the mountain and you must become Sisyphus, and put your back into a new ascent.

So, about four months after the release of Serpent Box, I wanted to quit. I wanted to burn all my notebooks and drag all my unfinished stories into the recycle bin and hit empty, because why write? What is the purpose of writing, of signing with a big publisher, of spending thousands of my own dollars and hundreds of my own hours building websites and book trailers and blogging? How can I be a father, a husband, an employee, a promoter, a writer all at the same time? Where do I even begin? Well, I know what Anne Lamott would tell me. Bird by bird, she’d say. You take it bird by bird.

It was the first book I ever read on writing. A slim, pithy volume of anecdotes, aphorisms and instructions that gave me the courage and confidence to begin a whole new life. Bird by Bird was my gateway into the writing life, or perhaps I should say the writing mind. When I read it for the first time in 1997 I had written a total of two bad short stories. I was no writer. But that didn’t matter to Anne Lamott. There was a writer inside me, and somehow she knew this.

Bird by Bird helped me understand many things about writing that I felt intuitively yet could not articulate or confirm. The struggle of a writer. The daily commitment to the blank page. The trust in the subconscious. The faith that, through desire, persistence and a humble dedication to craft, something worthy of reading would emerge from your heart. Anne Lamott humanized writing and writers so that I could believe I could do it and be one.

I’m reading Bird by Bird again, for the first time in ten years because I’m suffering a new crisis of faith. I’m having trouble believing not just in me, but in writing itself. Why do it? To what end? The publishing industry and the book business is so awful. It’s a machine whose mechanisms work against those who provide the product that sustains it. The writer who seeks to create something different, something non-commercial, something with a little soul, is in for a shock. I tell you plain the business of books has sullied my heart.

So here I am, reading this book that I turned to so long ago for direction and answers, and what I’m discovering is just how much of Bird by Bird stuck, how so many of Anne’s words and ideas about writing and story not only made it to the pages of my own work, but into the fabric of my writer’s heart.

In order to be a writer you have to learn to be reverent.

Yes. We humble ourselves before the world, before the page. We ask for direction and clarity and courage, and we ask it in the manner of a supplicant before his God.

Writing involves seeing people suffer and finding some meaning therein.

You write through the pain toward the joy. If there is no meaning to this why live at all?

Hope is a revolutionary patience…American novels ought to have hope.

Hope for oneself. Hope for mankind. Hope. A transformative belief in goodness and in the meaning of what we see and feel. And that all things do in fact have significance and lead toward a better understanding of ourselves.

Good writing is about telling the truth.

My truth which is your truth because all truths are shared.

There is a door we all want to walk through and writing can help you find it and open it.

You don’t need Prozac and you don’t need the booze. You don’t need a therapist. Answers are found sometimes by asking questions and you don’t really need the answers anyway. Just the questions are often enough. Writing is asking questions.

Don’t pretend you know more about your characters than you do, because you don’t…Plot grows out of character…Don’t worry about plot, worry about character.

And worry I did. Never letting the story control me, but letting its people. I wrote my first novel by watching and listening to its people.

Plot is: what people will up and do in spite of everything that tells them they shouldn’t.

Every single one of my characters wound up doing things that on its surface, seemed crazy. But it all made sense in the end and of course it could not have happened any other way.

Writing is about hypnotizing yourself into believing in yourself.

And I had to become a master hypnotist. Look at me now. I’m doing it again. I am devising ways to convince myself that I am worthy of this very small gift, and that I am sane. And I have discovered that many of the tools and tricks I use to cajole myself to keep going were given to me by a woman I never met who sat down like I did and wrote something out of her heart as a gift to those who would follow her down that treacherous path a writer of good conscience must travel each and every day.

Bird by Bird. Little by little. One step at a time, one day at a time. You focus your attention on what is right in front of you, right there, the small things. The birds are the things we write about, which are the things we care about, the things we believe with all our heart. And those things don’t happen fast. They don’t happen without strain and effort and patience and time.

(The) truth is beyond our ability to capture in a few words…(and) there will need to be some sort of unfolding to contain it, and there will need to be layers. Bird by Bird

Our living is like this too. We stumble upon great truths by gathering small ones. If we observe closely, with the most sincere humility, the people and the places that claim our attention through their proximity alone, through their seemingly random placement in our paths, we begin to see ourselves reflected in them. For we are not separate from any thing or any one.

This flesh is but a memento, yet it tells the true. Ultimately every man’s path is every other’s. There are no separate journeys for there are no separate men to make them. All men are one and there is no other tale to tell. Cormac McCarthy, The Crossing.

Why, in God’s name, do I write?

I write to help me discover and pull back the layers. I write to assemble in one place a series of relevant truths and thus understand something greater. About the world. About myself. I write as a defense against fear and doubt and yes, anger at the ugly, unjust world, but also I write to express joy at that same world when it is beautiful and just. I write to create small order out of this great chaos, and to rise above, or perhaps filter out, the din of this mad living. I write to remember. I write to see. And I only share it with you, with other readers, because I so desperately seek communion with those who believe in the power of words to change and transform and unify the living and the dead. Words, which are birds. Birds which are tiny, fragile things encased in feathers, things that defy the forces that fix us to the spinning earth, that hold us down, that hold us back. Words are the crude ciphers of a heart bursting with joy and confusion, the visible proxies of sounds that are cries of exultation and pain.

So out of my despair has come a new hope that is really an old hope, the hope that through words and language and story I can change a tiny part of the world, and this is the hope that started me on my writing path in the beginning. Because writing, true writing, is not about being read or published or sold, it’s about discovery. I have discovered again why I write. By going back to Bird by Bird, by going back to the place where I first drew a cup from the well, I have realigned myself with what is important about writing as a means of communication and a way of looking at the world.

This is a letter of humble gratitude to Anne Lamott. Who gave me courage, who stoked my faith. And I would like to give you, Anne, the product you helped me to create. I hope to meet you so that I can place into your cupped hands my little collection of birds, Serpent Box, my story about a boy in search of his faith, in search of his meaning. For he too is a gatherer of birds.

If anybody know how I can get in touch with Anne, I will send you as a thank you gift a copy of Serpent Box. VLC

[ view entry ] ( 4998 views ) | permalink |

( 3 / 3745 )

( 3 / 3745 )

A pen. But not just any pen. A Uni-ball GEL Impact 1.0 mm. Black. Or a pencil, if the medium is hard, if the writing is to occur on a table or a desk. If the medium is paper, which is pulverized trees. Lined or graphed and in a notebook without a spiral. Not loose. Not blank. The medium must be contained, bound in some manner as to keep pages from separating. You touch to connect.

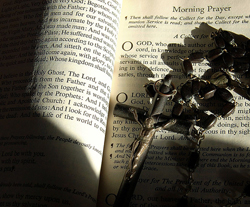

A bible. Small, leather-bound, preferably old, a hundred years and counting, and well-read, well-worn. King James edition. Musty-smelling and somewhat faded by sun, by eyes. A good used bible is a window into a another life. Another’s soul.

Rumi. Coleman Barks Edition. Bloated with bookmarks, festooned with 3M brand stick-on flags marking pages and passages and lines where, in times past, a certain unity had occurred, a joining, a reunification between the reader (myself) and the writer (Jelaluddin Rumi) and the translator (Coleman Barks), forming a momentary trinity, a new Pangaea, a super-continent of hearts and minds.

A small stone pried loose from Jack London’s grave. Mouse-sized and mouse-colored. Suitable for rubbing or total enclosure within a fist. It gives off a heat you can feel in your palm. A transference.

Bones. The ivory femur of a deer. Human metatarsals. A few teeth, molars, no dental work, likely from China. Various vertebrae. The scapula of a seal. A cat skull. A marmot skull, a fox, a raccoon. The fully articulated skeleton of a tropical snake. There was flesh here. There was living.

Dog tags. Tin. Some notched, some not. WWII, Korea, Vietnam. Unknown men, long gone. Closer to true identity now. Perhaps there is some power within them, some force I can harness.

Sea shells, acorns, owl pellets, Zippo lighters, bullet-casings, fossils spanning epochs and formed during catastrophic events, crucifixes, old rosaries. All objects of a peculiar faith. The talismans of a writer. Hand-worn things that bridge the divide between the living and the dead. They are, to me, proof of existence beyond myself. Beyond time. Toy soldiers, .50 caliber Confederate slugs dug from the hard-packed mud of Fredericksburg, pinecones, old photographs bearing unknown faces and graced with captions in floaty script, cigar boxes, envelopes stuffed with cancelled stamps, comic books, baseball cards and ticket stubs from games actually attended. The things I carry. The things I hold. Not on my person, but in my hands, sometimes, before the writing begins. During the writing. Little brass keys and thick foreign coins. Connections, proofs and signs. I am nothing without them. They help me to connect, to believe, to imagine other lives and also my own, once I am gone. Without them I am nothing.

How do you channel the un-seeable? How do you create a link between the unknown and the barely understood? How do you reconcile living? Writing as living? Writers look to printed words, and objects. They hold them, read them, take them into themselves. You write to understand living.

For me there must be a physical connection to the mystery of this life. A grounding. Small, fleeting answers to great questions. Who I am? What I am? What do I do with pen and wood pulp and ink? Combine them. Create living artifacts that require no translation, no guesswork. I Lived. Construct a conduit between the living and the dead. That which was and that which is to be. And this is how it is with the snakes. This is what a Holiness man does with his serpents. He connects to his God.

A Kentucky preacher, Pentecostal, arrested just last week for trafficking snakes.

(http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/25651899/

Dozens of snakes confiscated. Donated to a local reptile zoo. These snakes were the implements of this man’s faith. They represent his link to his God. Holiness Pentecostals, Sign Followers as they are called, believe in what Jesus says regarding faith and the Holy Spirit. He said that those who believe are protected. He said that those whose hearts are true can, when filled with the Holy Spirit, withstand venomous bites and the consumption of deadly poisons. I believe this to be metaphor, but it doesn’t make a difference what I believe. I have my own bizarre rituals of faith. The Holiness people believe this to be literally true. Theirs is a religion marked by a visceral connection to God and that the Holy Spirit is the manifestation of God. When they handle serpents or drink poison they are proving to themselves that God is there, with them, in their flesh. Proof of God. Imagine. This is beautiful. This is sane. Wanting this, now, in this world, makes perfect sense. Are you with me God? Are you there? Touch me. Hold my hand, stroke my head. Protect me from death because, sweet Jesus, I am so damn scared of living.

Why must we take away their snakes? Why is religious serpent handling illegal? Why not let these people alone? They are simply trying to connect with God. They are trying to find some meaning in a life which has become increasingly besought with violence, hate, greed, selfishness and fear. If a snake can do this then let them keeps snakes.

Snakes – the very symbols of sin, the darkness, the duality of man’s spirit, a reptile, primitive and cold-blooded, from a wholly different world, a different time, before the onset of man, a creature sleek and simple and perfectly designed to fit its niches, a beautiful product of evolution, but also a creature so misunderstood and cast so undeservedly into a role of malevolence. This organism is a perfect conduit to faith. Because it is a metaphor for man.

Pentecostalism is the fastest growing branch of Christianity in the world. Not the snake handling variety but the tamer, safer version that simply focuses on the Holy Spirit. And it’s no surprise. In how many other places can we find a visceral connection with a higher, benevolent power? Pentecostalism so named for Christian Day of Pentecost, which occurs fifty days after Easter, and in the Book of Acts, that first Pentecost marks the beginning of the Christian church and faith. On that first Day of Pentecost, the bible says, the Holy Spirit reveals itself as an omnipresent helper and spirit of truth. It was the Holy Spirit who appeared to Mary and the apostles on the day of Pentecost to affirm the resurrection and their faith.

The Holy Spirit. You don’t have to believe in Jesus or God to appreciate the notion of something inside and all around us that we can feel. And if you pay attention you can feel it, without snakes, without bibles, without mass or worship or prayers. You don’t need religion to feel connected, looked after or loved. You don’t need miracles performed from above when you have miracles performed here, all around you every second. The continuous unwinding and reforming of DNA, the birth of a child, a spider’s web, the human mind.

Einstein said:

“My religion consists of a humble admiration of the illimitable superior spirit who reveals himself in the slight details we are able to perceive with our frail and feeble mind.”

And:

“That deep emotional conviction of the presence of a superior reasoning power, which is revealed in the incomprehensible universe, forms my idea of God.”

This is my idea too. God is nature. God is the universe. And I can feel it, without my tangible crutches, my scrounged and collected implements of faith. But I want those things, as they are the comfort food of my soul. I want my bibles and my bones and my snakes. Because simply seeing them reminds me that I am not alone.

[ view entry ] ( 10308 views ) | permalink |

( 2.9 / 5828 )

( 2.9 / 5828 )Please forgive me. I am humbly in awe of what the universe will provide if you ask for it. I have been feeling very down, very sad, because the world of book publishing, the business of it, is so cold, so short-sighted, so cruel. I have been thinking seriously of giving up. Never writing again. And then comes this, this lovely letter from a reader in the midst of Serpent Box. Here's what he says:

"In the train, I’m sitting next to a woman who’s reading a business book called “The Case For Levity”, opened to a page with a little text box that says, literally, “8 Questions for Measuring a Potential Employee’s Fun Quotient”. Ha! I’ve been waiting for the Slaughter Mountain chapter since Monday...I’m beyond questioning you as an author – you’ve already earned my trust as a reader, and since you’re a craftsman I will digress briefly and tell you specifically how you did it to me. Each of these ‘checkerboard chapters’, the Ten Years Earlier section, has a payoff. At first glance, I thought “Ten years earlier? Oh noooo! I’ve got to wait until I find out what on earth happens to Jacob!”

But you make it easy to wait. Every chapter illuminates something vital in his parents’ lives, something meaningful and interesting. You don’t betray your reader. Every chapter ends with a feeling of dawning enlightenment, and I know that it is purposeful and intentional. And then, somewhere around the nighttime box car incident with Charles and Sylus, I was content to leave Jacob on the back burner, lying bitten in the Tyborn tree, because I already trust you. And all of a sudden, I’m more interested in Charles and Rebecca than I am in Jacob. A coup for the author!

Our Sofia was born at home, by the way. Jacob’s birth rang true to me. I recognized it. I knew, when reading it, that you were a father. I tasted a little of the love you have for your daughters. It echoed and resonated with the love I have for mine.

So, to resume what I began in the first paragraph: I’ve been waiting for Slaughter Mountain since Monday. A good waiting, a getting ready to savor a good meal kind of waiting. And you pulled it off for me. I don’t see any of the work you put into it, edits or revisions or doubts. I know the work that goes into crafting something, and I know how difficult or impossible it is to come back to it later, separate from the experience of making it. But I’m telling you: from the outside, it flowed. Easily, perfectly. I forgot I was reading, I forgot I was on a train. You pulled me out of myself and landed me in the crowd under the circus tent, and I was a spectator, and then, as in a dream, I was Charles, or perhaps just behind him. And then I was the boy, with a tamed rattlesnake in my hands and filled with the spirit of the Holy Ghost… as I was in my mother’s high octane Pentecostal church, drizzled with oil, speaking in tongues, and watching the casting out of demons.

You pulled me straight out of myself, heated me in your poetic prose, pounded at me and molded me and then sank me in the ice bath of my own memories, and you made me different. Your writing changed me, man!

I always used to joke that my mom’s church was just one level below snake handling. It is a bizarre and wonderful experience to have you leading me down this road you’ve built.

Thanks for writing this book. It’s marvelous, it feels just right to be reading it, and I am happy to know you. I don’t know what kind of difficulties you’re facing today, but if you ask me, you should let ‘em go. You’re an author, and your book is out there doing good things to people. Everything else is just details.

I can’t wait to keep reading!

Daniel"

THIS, dear readers, is why I write and why I will keep writing, as long as you let me. As long as you will keep reading.

[ view entry ] ( 8841 views ) | permalink |

( 3 / 5278 )

( 3 / 5278 )

Random Entry

Random Entry